© MECC (1994)

When I was growing up, in the greater neighborhood surrounding the cul-de-sac I lived on, there was a house at the top of a hill I often rode up on my bike, bookending the upper avenue. In the front yard, there was an old well.

It took me several passes by to even notice it, under the shade of a large tree, half-hidden by several overgrown bushes. Thinking back on it now, I can’t begin to imagine how it had come to be there — the housing development was younger than me, had grown up around me; when my parents bought our house, there was nothing around us but dirt, my future high school, and a gas station — or who might have dug it out. So high up on a hill like that, could it even reach any sort of aquifer? It must be just for show.

But no; I looked around to make sure no one was watching, poked my head in, threw a sizeable rock down, and could barely hear it hit the bottom. It was real. Empty and purposeless, but real.

I maintained a sort of detached obsession with it for some time, in the sense that I never actively thought of it unless I was riding or walking by, but would often insert an 8-bit avatar of it into the background of a page or two when playing around on one of my favorite computer games in the grade school library during recess: Storybook Weaver.

In hindsight, it would make perfect sense that the a program held such a fierce appeal to me, that I would return to fiddle around with it so regularly. It offered the illusion of crafting any story your imagination could dream up, but in reality was hemmed in by any of the familiar limitations of software programs of the late ’80s and early ’90s. There were limits to the objects and people you could choose from, there was a fixed number of scenic backgrounds in which to place them. You could change some of the colors, or the time of day in which they were set, but ultimately, before long, every page took on a fairly familiar cast. The challenge lay in creating something original from within those parameters.

How often have I wanted to believe I could craft any narrative I wanted from preexisting people, places, conditions? How often have I tried, yet come up against walls so similar to those written into that old code I was once enchanted by?

Do you want to save the current story before closing? [ ]

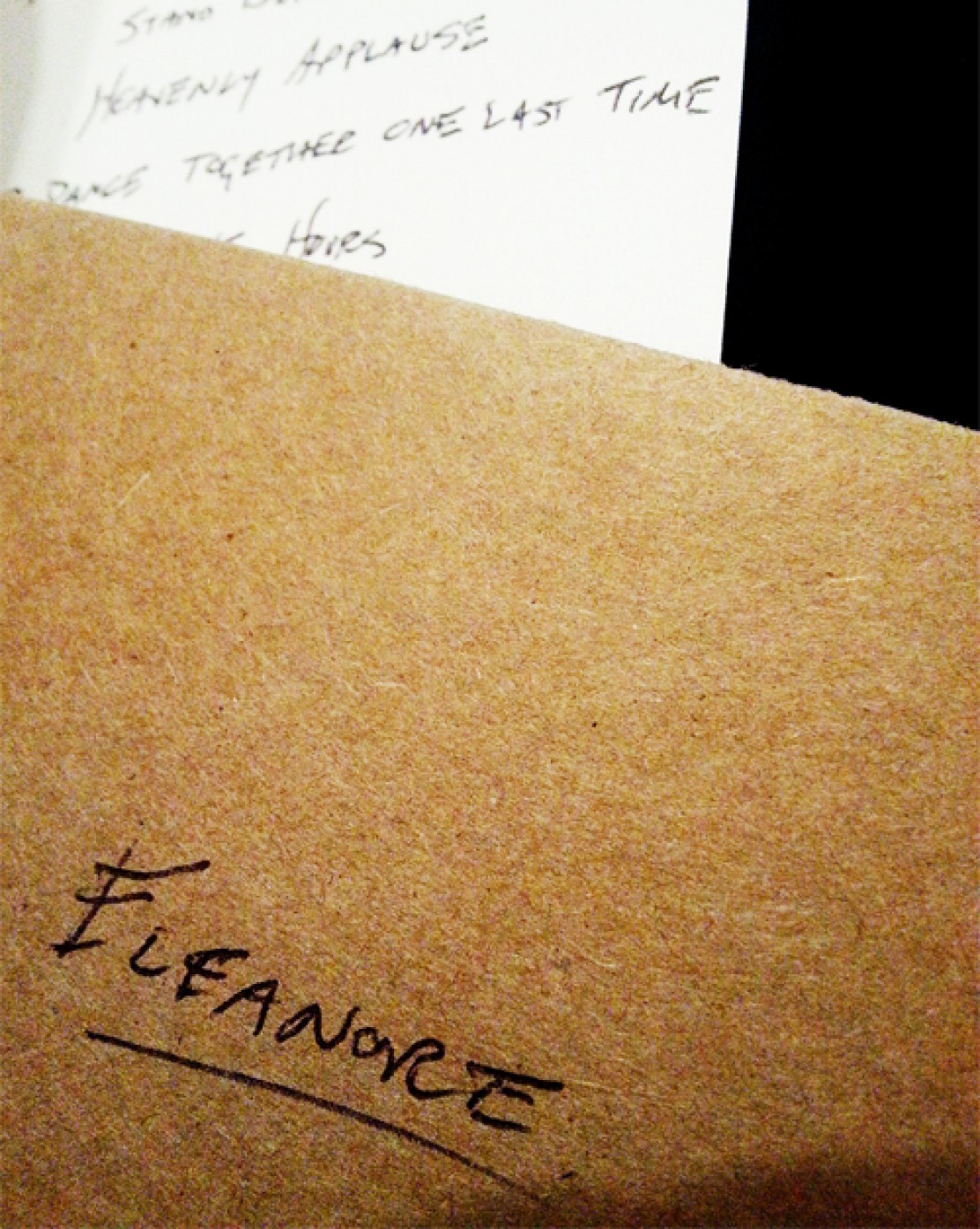

I always saved. Even when I’d added little, rarely finished, and had no floppy disc of my own to write to — we wouldn’t have a computer in my home until relatively late, around 1998 — and knew in a rather mortifying way in the back of my mind that anyone else who logged on had the opportunity to go back and read whatever I’d made. I always saved. I saved everything.

I still save everything — in boxes, written into Word and Notepad documents — though what for, I know no better now than I did then. So much of it only staying with me, so much only saved by me.

Six years is a long time, and yet eventually becomes no time at all. It passes, circumstances change, things are broken that can’t be repaired, are papered over by mere shadows of their former selves. Looking back provides better perspective, though not always for the better. The lone saver of things can be a lonely position to turn back from.

So much thrown down an empty well, up on that hill, never to be reflected back.

Start a new story [ ]

Choose a story to finish [ ]

Choose a story to print [ ]

Choose a story to read [ ]

I’d like to quit now [ x ]