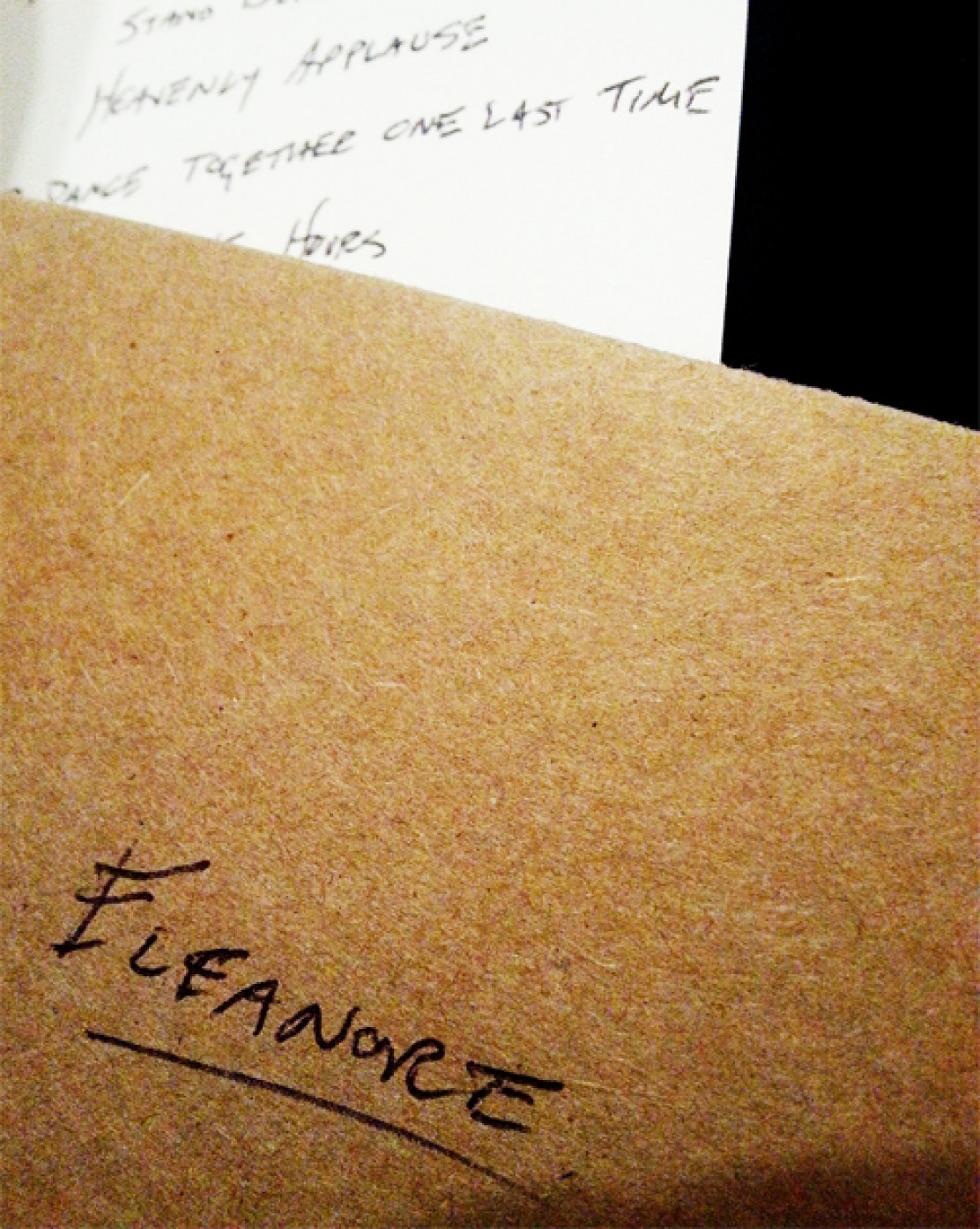

I wrote about my mother first; this must, necessarily, be about my father.

Why is it the men who raise us must inevitably, inescapably shape the ones — friends or otherwise — we allow to ourselves to love later? How long have we been musing on this overly familiar pattern already? How can it still be such a clever trick?

Windows, or mirrors? (2 February 2016)

Distant, withholding, critical — sometimes thoughtlessly cruel — impossible to please men. Men talking up all their pride in you, while doing so little to demonstrate it, as if words alone are enough to swallow up such yawning absence of genuine action. I could only grow to constantly question any sort of love now, after being raised, shaped — groomed, even — to find myself wanting in my father’s eyes first. He left, went off far away, then wanted me to explain why he was alone. I don’t know, Dad; I can’t even tell you why I’m alone. You decided you belonged nowhere, and with no one, and so that became my lot in life, too.

Though I suppose I could. I could have written my younger self a letter. I might have said: Watch out, watch for all the ways he looks to control you. They are shaping you now, have already shaped you, will shape you always, no matter how much distance ends up between you. He does love you, but there are conditions, ever-moving goalposts, impossible standards. All of these will trip you up, again and again.

I might say…

You were the one who survived — though he never told you this, you had to lie to your mother to even learn that much; the other family who died, and you, the sole surviving child — but simply continuing to breathe, taking up some small space in the world, this is not all that will be required of you, of course. You will never ask to know more.

His pride is a performance, only expressed to strangers; to you, there is only more criticism, more questions to put you on the defensive, more requests that you justify yourself, again and again. Watch carefully, before you begin to feel you must justify yourself to your own mind, too.

You will miss school, your student years, sometimes: the only time and space in which, and audience for whom, you have ever managed to exceed any expectations. Elsewhere, you will only ever fall short. All that performative dismay over so much imagined potential.

You will grow up, and there will be other men, and you will not be told the reasons, you will only see their effects. Watch closely for all they hide and take from you, and how relentlessly they try to test your determination to grasp those unreachable rewards. Sometimes it will be merely distance and poor timing, or the fear of interrupting fantasy with reality. Other times, you simply aren’t attractive or interesting enough, when you are of notice at all, though they may pretend otherwise, for a while. (This is why you will wonder, always, whether they mean one single word of it. Do not expect them to understand; they won’t.) With a few, they will shower you with all manner of compliments and admiration, but only when they don’t know you well enough to know better; it’s no coincidence the most effusive are the ones who know the least about you.

And sometimes, you will be close, closer than you could’ve imagined… Until you aren’t. You’ll turn to find your place papered over so neatly it’s almost as if you were never there. There’s nothing quite like the feeling, like that of your insides being slowly scooped out, of watching the shine come off yourself in someone else’s eyes. (What happened? You’re still you. Where did all that brightness go?) You may never know why, but you’ll see for yourself just how dull you look to them now.

Your seemingly innate inability to accept compliments or praise, the withholding men you’re most drawn to, your hawkish loneliness, the secrets you keep…

Your want to be understood, to be seen, to not be so easily forgotten, to be accepted, to belong; all that wanting, take care to familiarize yourself with that ache…

Wanting, wanting, wanting: All you will know is wanting.

No angle of your face will ever be beautiful enough, no arrangement of your body desirable enough, no amount you give adequate enough; all that straining to be…

Enough, enough, enough: You will never be enough. Don’t forget.

I might say — or might have said — those things. But then again, I might not.