I had just finally managed to calm down from driving around, going nowhere, trying to get the rest of the unexpected bloodletting over within the too-familiar, protected, isolated confines of my car, only to come home, check my email, and find a message from my mother. It had, of course, nothing whatsoever to do with anything on my mind at this moment, but simply seeing her name highlighted in my inbox like a beacon prompted me to burst right back into tears. At least all my mascara for the day is already gone by now; I still hate how puffy my face gets.

When I was younger, and clashing the most violently (emotionally and verbally, that is) with my mother, I was extremely determined to never become like her. This is, of course, one of the ultimate teenage tropes that’s likely existed since the dawn of humanity, but when you are young and feeling everything at your highest intensity, it feels both very rebellious and extremely important. (I imagine this is why I, along with so many others, was so unexpectedly moved by Lady Bird, recently. The tone of those mother-daughter fights was so exacting and familiar — coupled with the very pointed and accurate outsider rendering of what it’s like to grow up on the poor side surrounded by so many bizarrely exotic rich kids — I felt deeply shaken by it.)

I would not be like her. I was positive — growing up under the burdens laid on a gifted child, always being told about all the great things I would supposedly someday do (none of which have ever come to pass, of course; do they ever?) — that I was smart and resourceful enough to make sure of this.

In reality, of course, I get many of my best qualities from my mother. I certainly inherited her self-sacrificing nature, particularly when it comes to bending over backwards for the sake of those I care about, whether or not that’s even the good or right thing to do in a given situation; the general lack of a vetting system to go with it comes from her, too. But that is a stowaway risk inescapably bound to big-heartedness, and accepting that, as I’ve grown older — about both her and myself — has become easier. What I struggle with more, these days, is forgiveness. Not of her, either; no matter how much we fought back then, or how crazy she could drive me, I’m old enough now to recognize she sacrificed as much as she possibly could simply to protect and elevate my life, in the hopes that it could be greater, happier, more fulfilling than hers. (She continues to find ways to do this, even now that I’m in my thirties.)

She did not want me to struggle, like her. She did not want me to be trapped, like her. She did not want me to end up alone, like her.

Unfortunately, I also recognize how badly I failed her, in those hopes, completely across the board.

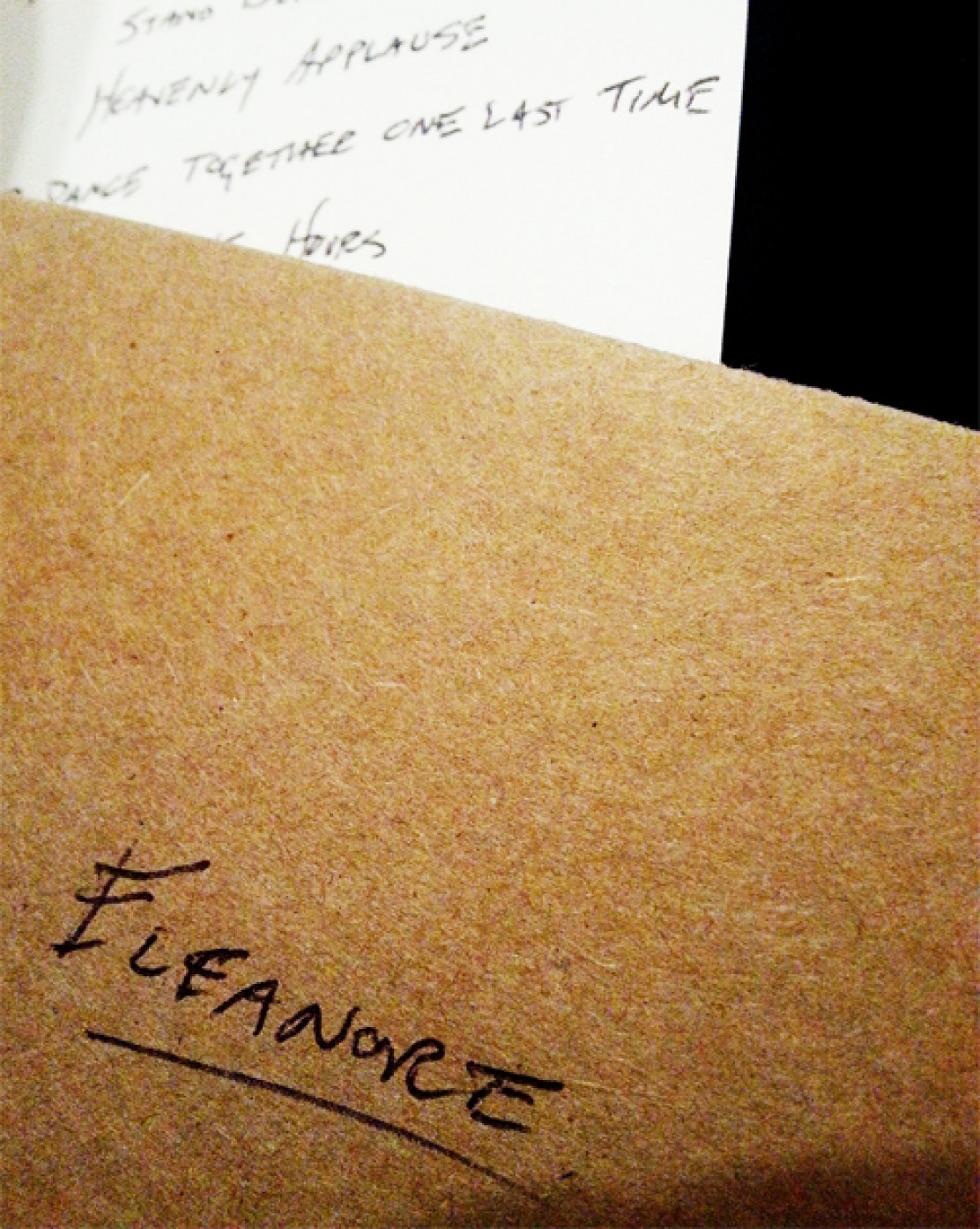

My mother’s hands (2013).

Younger me was certain I would make it further in my education, and knew it was expected of me. I did not: my mother only ever took one college course (I believe it was French, at UCLA), during her earliest years in California, and never finished. I dropped out of (community) college a mere 3 credits (a single online course) away from graduating. Arguably, one could say that’s even worse. I wouldn’t disagree, I don’t think.

Younger me was adamant I would never end up stuck in a soul-sucking office job like hers, constantly fighting to meet the demands and satisfy the flighty, shallow whims of an endless string of horrible bosses, as she’s now done for over 30 years. Once it became clear, in the past decade or so, that the professional avenue she had chosen was nowhere near as “safe” or protected as she (and so many others) had always believed, I certainly was not happy, but some small, ugly little part of me did feel at least slightly, quietly justified in never accepting a similar job, though by now I’ve been working over half my life. (There were other reasons: it’s not work that I’m suited to, I’m far less flexible in what I can tolerate at work and separating it from my overall mental health than she is., etc..) I had stuck to my guns, and always (where possible, which it sometimes wasn’t) taken jobs that I wanted to do, whether they paid well or not (and they usually didn’t), that allowed me to keep my creativity alive. At the very least, I was never anyone’s secretary; I had drawn that line in the sand, and would never cross it. I knew she felt regret at having given up on art and writing when she was younger, before fully devoting her career to administrative work, however well compensated it might have been. I thought to myself: I will not have those regrets.

Does that make it ironic, then, that I see now that I did in fact end up just like her, merely in the one way I could not have anticipated? I’m sure it does. I struggle to stay afloat just as much as she does, so we’ll (perhaps generously) call that one a wash. I am trapped, like her, though not by my work. I am alone, like her, and in almost exactly the same way. And I suspect, if I were ever to admit this to her, that would be the one thing she would have wished the hardest for me to avoid. But I didn’t, of course. I am trapped by, and remain alone because of, nearly the very same thing that she was, and still is. Even if there is no possible defense for such a thing, I’m still astonished by the breadth of the blind spot I had been operating under for so long. I genuinely believed that, in achieving what I have, I had escaped what she wished for me never to have to bear.

I’ve achieved plenty, too. I’m still managing to keep a roof over my head. I have a stable job (much more so than hers, which at this point I just wish I could share somehow; she is reaching an age where I seriously fear where, or even if, she might find more solid ground ever again), and it’s one that I genuinely enjoy. I’m embarking on an exciting and creative new journey, too; one that feels very much like the culmination of something I was meant to do long ago, but had forgotten. I love my city, and my friends. I have done a good job of making my own home in the world. I have support and rewarding relationships around me. I have yet, still, to have a bad day this year. Even today, I can’t log as a bad day, because I seem to really have rescued myself from whatever hole I kept burying myself in last year; it was just (deeply) upsetting. But I’ve gotten through it, I’ve finally stopped crying, and tomorrow will be fine, too. I trust, finally, that I haven’t lost anything irreplaceable; only my one remaining secret, and a considerable chunk of my already rather small stores of pride.

But despite all of this, I was not spared sharing her most enduring pain, in ending up caught by my own. And I do struggle with forgiving myself, even now. I don’t know how to forgive all the arrogant and shortsighted assumptions I made about her, and myself, back then, knowing now how wrong they really were. (Yes, I was young and dumb. I’m not sure how adequate an excuse that is.) I don’t know how to forgive myself for expressing things I never meant to let out into the world, which I could not protect myself from, any better than she could protect me, and not for lack of furious trying on both our parts. Funnily enough, I am now the very same age that she was when she was either doubling down, or realizing and accepting it was already too late; I know now how she must have felt. Five years is a very long time to punish yourself for anything, no matter how foolish or pointless that thing may be, but that did not stop me, and still does not stop me even now. I am, after all, much more likely to cry out of anger or frustration than I am out of sadness, though in this case it’s that awful mix of all three. I suppose what this all means is that, as much as I’ve already been inspired by her tremendous continued survival, I must continue to look to her for understanding how, exactly, one lives with themselves this way.

I don’t hate myself. I’m all right. Often, I’m quite happy. It’s just… I genuinely believed, for a long time — in part, I see now, because she did — that I could’ve been so much better.

I did want to be so much better, Mom. You had only me, and you deserved better. I know you wanted that, too. But I also know how little wanting or hoping has anything to do with what you get, in the end.

And I am sure, at least, she would not need me to remind her of this, either. She already knows.

via Daily Prompt: Provoke