(Today’s WordPress prompt is slowly. I made my up this old street, through these memories, and through these photos, especially: slowly.)

I think back on these people now as the first and last neighbors I will ever have. I simply have no reason to anticipate ever inhabiting a neighborhood like the one I grew up in again. There will certainly never be a day when I own a house, and the neighborhood I was raised in was comprised entirely of them. The people who surrounded me as I grew, who I came to understand and recognize as my neighbors, were a part of that environment, and do not exist outside of it; they are only of that place and time. Since then, I’ve only resided in apartments, or my mother’s condo. She knows some of her neighbors now, but they are not mine. Even in the six long years I lived there with her, in much the same way I never made the room in that condo my own — never finished unpacking many of my possessions, never organized things in a more pleasing manner, never hung anything on the walls — those people were never my neighbors; they were hers.

I drove slowly up and around that cul-de-sac, and was overcome by the knowledge that there was no one there who would know me. The sole remaining family from the 20-odd ones I once knew was not at home; the garage and windows were closed, no cars parked out front, no signs of life within. Even if there had been, I’m sure I wouldn’t have stopped my car, let alone gotten out, walked up to the door, and knocked. If the man who used to fondly call me “Nori” were there, or the woman whose young son used to do his homework under my watchful eye had been at home, I don’t expect either one would have recognized me. The last they had seen me, I was a fresh high school graduate; tall and still rather rail thin, with the only curves to my appearance still lingering around my face. My hair was long, blonde, and messy, down or habitually tied up, stuffed away at the nape of my neck. It was nearing half my lifetime ago, and I would have been a stranger. Nothing of me was left.

I drove a slow lap, marking each house as I passed it. Next door to us, one of the few single-story homes on the block, was Irene’s house. She had long since moved away — I wasn’t even sure whether she was still alive, a realization that filled me with a mixture of guilt and dismay — but I could only think of the house as hers. Hers was the living room in which I had sat on the area rug, petting her old mutt whose name I had forgotten, but whose soft, matted fur I remembered still; hers was the kitchen sink in which I had washed out her watercolor paint brushes after watching her fill a canvas with a precision I would never have, longing to be a painter myself, knowing I never would be. Hers was always the first door I knocked on as a Girl Scout, knowing she would be delighted just to see me on her front step. Hers was the husband who died when I was only four; who I knew would die the day before, standing in our guest room — which would later become my mother’s, after my parents separated — looking out the window in the late afternoon light, seeing him standing in the driveway. My parents hadn’t yet attempted to explain death to me, as much as you can ever explain it to a child, but standing in that room, looking down at him, without him seeing me, not even knowing he was sick, I knew he would not see him again.

The next door down had housed a family from Switzerland, so naturally my father had immediately befriended them, despite their having come from the German part of the country, and my father coming from the French; his nationalism never wavered in the face of any other factors. The father was odd, but he is the only one I remember, because I had worked for him for a summer, attempting to organize his extraordinary mess of a home office. Struggling to alphabetize his folders in their clunky filing cabinets, often having to guess at the first two or three letters of words, because his handwriting was all but illegible, and if I ever guessed incorrectly, he never told me. From one day to the next, he would change his mind about how he preferred his books to be arranged; one day by author, the following by title, other days by subject, and so on. He was paying me, and I have always loved books, so I didn’t mind moving them around all over again. I could sense I was glimpsing the remaining fragments of an unusual and perhaps extraordinary life, given the evidence in those drawers of the places he had been and the things he had done. I remember he was fond of me for being a reader, and for playing the guitar, which he had once taught himself. Apparently that was all it took, though I could never say I knew him, let alone the rest of his family, well. Of his wife’s face I have only a vague impression now, framed by her short brown hair.

The next house was the Day’s, and the aforementioned last standing of the original families, or so my mother had told me. Their older daughter Allison’s room was where I had once sat and listened to “Hummer” for the first time on her cassette, on one of the few occasions she ever acknowledged my presence in the house, before I was old enough to look after her younger brother Tyler. Thinking of him made me ache now; the last I’d heard of him was that he had fallen away from his family and into heavy drug use. I still could only think of him as the best behaved child I had ever babysat, and my favorite. I looked after him long enough that we established a routine; the same bus that I had once taken to the same grade school would stop at the end of the street, drop him off, he would walk up and let himself in the front door. I would be sitting in the living room, doing my homework, waiting for the sound of his key in the lock, and his endearingly, extremely low voice announcing “Hello,” to me and the house. He would make himself a bowl of Rice Krispie’s cereal, with a heaping spoonful of brown sugar on top, watch cartoons for a half hour on the floor between my feet, then go upstairs to his room to do his homework. He would bring it to me to check over when he was finished, and then ask my permission to go outside and play. The house was situated in such a way on the street that when he did, I could see him through the living room windows, and make sure he was safe. For a brief period his parents had attempted to use Ritalin to curb his attention deficit disorder, which apparently caused him to struggle in school, but all it did — and this hurt to remember, too — was turn him into a shell of a person, all personality, energy, and feeling removed. This experiment didn’t last long, thankfully, but I couldn’t help but think of it now, passing his old home, and wondering how that might have informed the place he found himself in now, and I had to turn away.

The next house had never had children attached to it, as far as I ever knew, and as a result, I never knew the inhabitants well. On a small street with 26 kids apart from me, it remained quiet and separate. The next belonged to my childhood best friend.

Josh had been born almost exactly a month before me, and his mother and mine were friends — and later, the church-going kind. Dawn often played Christian rock cassettes in her huge blue minivan when driving us to school some mornings, when one of us was too late to make the bus. They had us play together as babies while they talked in the evenings, and I do not remember a time, as a child, that I didn’t know him, his sisters, his parents, his backyard, his house. It all seemed to exist as simply a phantom extension of mine, as if the four houses between ours were not really there. His much older half-sister was a model, and a former Chargers cheerleader. His younger sister, Elisha, was a tremendous brat. His father was our baseball coach, when we were a little older. Dawn was the fiercest Tetris opponent I ever played, and I only ever managed to beat her once. Their garage never served as one for as long as I can remember; it had been carpeted, outfitted with a couch, shelving, and laundry room amenities, and the garage door was only ever closed at night, after the last member of the family had gone to bed; the rest of the day, kids in the neighborhood were free to wander in and out freely. The only video games I ever played as a child were played there, never having owned a gaming system myself. We played with his Batman figures and little green army men on the floor; we ran through the house playing extremely rough tag when left alone in the house, searched out junk food in the pantry, and watched crap on TV. We listened to comedy bits on cassette in his room, and climbed out his window to sit on the roof above the garage, which my mother never knew (and probably would have killed me for). We raced, bobsled and luge style, on his skateboards down the incline in the street, flying around the bend leading out to the bigger road, somehow not breaking anything or killing ourselves, ruining the soles of our sneakers, when we bothered to wear them at all.

His father had dragged out a regulation height basketball hoop to the head of the cul-de-sac — long gone now, of course — and we would play street hockey, HORSE, and small, short, half-court pickup games out in that communal circle outside his driveway. Without the hoop in the center, the street seemed lonely and empty, now. The yards were all different, too, and that in its own way felt like a loss. I had spent so many afternoons and nights, running back and forth between our houses, through the front yards, to my mother’s chagrin, so often, and so precisely, that I had worn with my long, athletic strides on my sure (usually bare) feet a perfect path between bushes, patches of dead grass, driveway, and front garden wall. I ran it so often I could have done it blind, but by now that was long since erased, too.

Next to Josh’s place was one that had housed a few families over the years, but I only really remembered Jaqueline, who I had tutored in reading when I was 12 and she was seven. Her parents ran a salsa company on the other side of the border, where they had moved from, and would often bring back baskets of the best green apples I have ever tasted. One year they were the house to host the block Christmas party, and, wanting me to learn something from her for a change, she taught me 16 standard Christmas carols on their piano. She seemed just as proud of me for playing them at the party that night as I was of her for all the progress she had made, though I would never play the piano again.

The most changed yard on the block, I noticed, was the one that had belonged to Chris’s family, another young boy I had looked after, and probably the next best behaved after Tyler. I had him to thank for becoming a fan of the Harry Potter books, as one night in the summer of ’99, he asked me to read the first chapter of the first book to him when he went to bed, and I stayed up to read the rest of the book before his parents came home. If I was looking after him on a Saturday night, I’d let him stay up late and we would watch SNICK. The best part of his house, however, was the humongous bush that had been planted in the front yard; a bush so huge, everyone had assumed for years it was a large tree with very low branches. On summer nights, after afternoons filled with water balloon fights and NERF gun wars, all the kids would drag various broken down cardboard boxes and pieces of old furniture into the darkness and play flashlight tag. The spotter would always climb up into that bush as high as they dared, armed with the high-powered camping flashlight, while the rest of us scrambled from one driveway at the crest of the street to the next, hunkering down together in bunches to avoid the light sweeping over us.

Most of the other houses on the opposite side of the upper half of the street I didn’t know well; the children who lived in them were younger, the parents not as close to mine. I’d recognize all of them during holiday block parties, but I don’t recall their names now.

Just across from ours, though, was Bill and Alice’s. It was the largest lot of property on the street, and Alice had taken full advantage of this, transforming the backyard into the finest garden I’ve ever seen, of the caliber that could’ve been — and was, at times — featured in a magazine. There were massive trees, rows upon rows of rose bushes, dozens of flowers whose names I never learned, patches of space dedicated to growing tomatoes, strawberries, and every type of herb; stone footpaths, even a couple of benches to sit on. She would let me come over whenever she was home, and I would often play around in the flowers, when I wasn’t sketching them. One afternoon I spent hours attempting a full picture of the entire garden, breaking all artistic rules of space and perspective to cram a sort of warped interpretation of a large place that seemed truly magical to me onto a single sheet of paper. She framed it and put it on the wall of their library, where Bill, a well-known local author, had put together a wonderful collection of books.

Next to them was the house that my first cat had come from, where Kris the real estate agent had once lived, who spent her off time rescuing boxes of kittens from shelters, raising them until they were old enough to be given away to good homes. After she left, the Jones family moved in, who I often pet sat for when they would go out of town; happily looking after their big, dumb Labrador, their skittish, soft-as-a-cloud chinchilla, and their oldest son’s python.

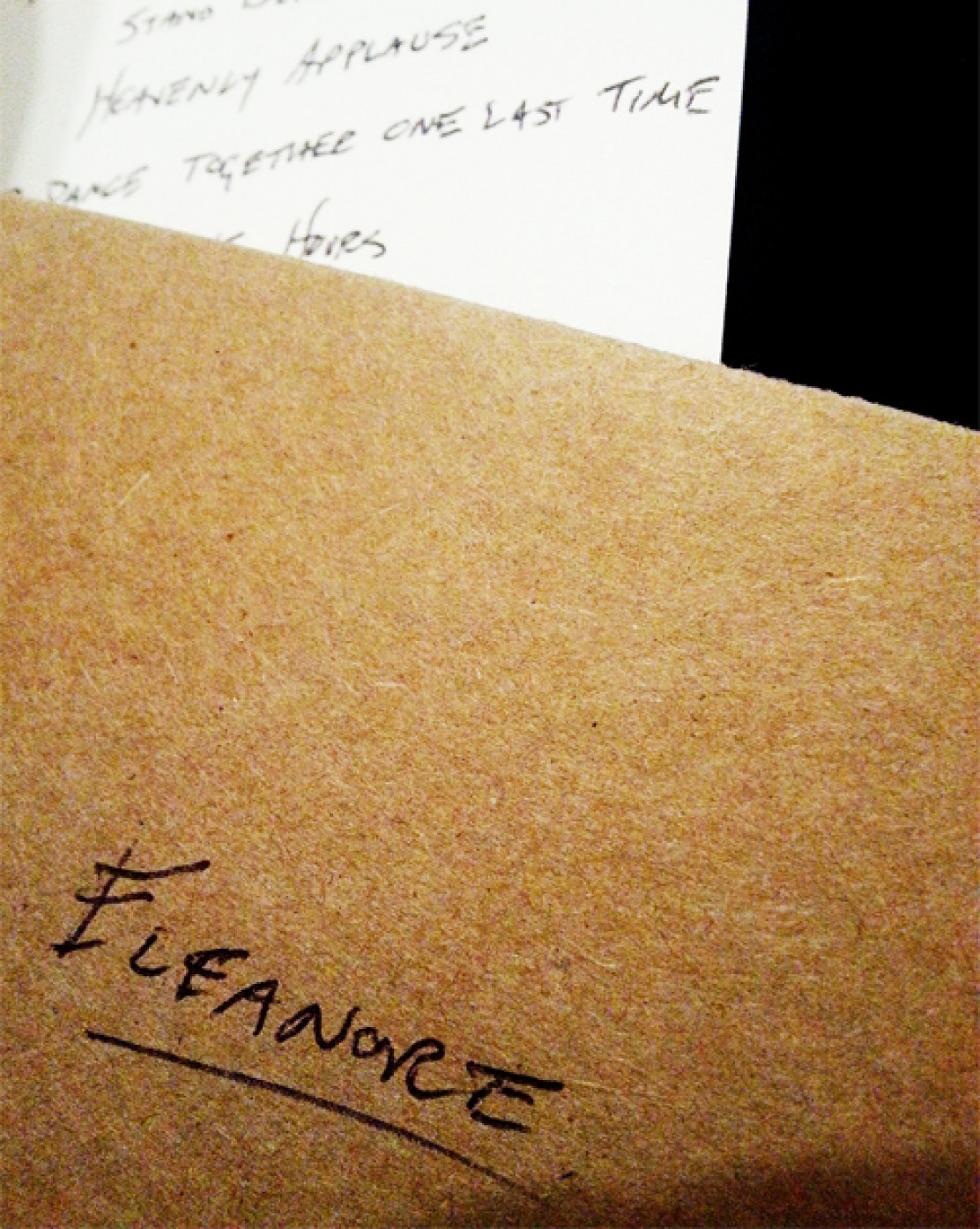

A couple more childless houses I never saw the inside of much followed, then came Alex’s. As Josh and I grew older and grew apart, Alex moved to the street, and became my closest (female) friend in his place. Like me, she was a tomboy, though more brash and reckless. Though I didn’t come close to feeling anything like love until I was much older, I developed an embarrassing crush on her older brother, Dan, who had a garage band, and used to invite me to sing when they would play. I sang Fiona Apple songs when I was still a bit too young to appreciate their content, because I could mimic her closely, and wished I were older than I were; even then, wished someone might notice me. (He didn’t, of course. For much the same reasons why I’ve never been the recipient of flowers, jewelry, anonymous letters, or any gesture even mildly romantic — when I was younger, let alone now — I remained as much under his radar as that of anyone else, anywhere I went.) Fortunately, the crush didn’t have much potency to it, and didn’t last. Alex’s was the tiny back yard in which I first experimented with putting any effort into my appearance, attempted in any way to be girly. She would style my hair, put make-up on me, and we’d photograph each other as if we were models. We made silly short movies on her father’s camcorder, an activity that came to an abrupt end when, under her dramatic direction, I fell backwards out her bedroom window onto the roof of the garage, cracking three roof tiles with the force of my spine slamming into them. We would send each other “mail;” hand writing short, almost pointless letters in made up, pre-teen girl code, running up and down the street and stuffing them in one another’s mailboxes, giggling as one of us raised the red flags, so the other could look out her window and see there was something waiting.

There are more houses on the block, and one more down toward the corner, but none of them hold any lasting memory for me. It is just the right time of year to drive back through here; just before Halloween, when all the yard decorations have come out. Living on a cul-de-sac full of kids, within a much larger, circular street that housed even more, was prime territory for enjoying my favorite holiday. We all ran around in groups — my parents away on their anniversary dinner — knowing which houses were the best (particularly the woman at the end of the outer street who cleverly gave out cans of Hansen’s soda) for what sort of candy, which had haunted houses hiding in their garages, which yards we could tear through without being yelled at. I was strangely reassured to see that one patch of solid grass remained exactly where I remembered it, one I remembered running along with Alex for years, on our way to the housing development that was coming up across the main street, where we would sneak into the three furnished model homes when realtors weren’t around, coming up with elaborate fantasy lives that only existed then and there.

I circled back around and finally stopped at the place I’d saved for last: my old house. The front yard had been rendered nearly unrecognizable; a gangly, garish palm tree, of all things, now towered over it.

I circled back around and finally stopped at the place I’d saved for last: my old house. The front yard had been rendered nearly unrecognizable; a gangly, garish palm tree, of all things, now towered over it.

All the grass had been torn out, and the beautiful eucalyptus trees that had been planted just before I was born, that I’d watched grow with me to tower and fill with murders of crows, had been torn out just after we’d sold it. The hillside looked bare and wrong without them, but the wall surrounding the backyard was exactly as I remembered it.

A five-and-a-half foot high wall of clay brick, I had stubbornly begun climbing it every chance I got, long before I was tall enough to see over the top, running along its narrow edge, terrifying my mother but never falling, sitting upon it and reading, blowing bubbles, watching the cars and people — the world — go by. I pictured the yard behind it, and could almost see it; the patchy grass my mother would drag our plastic kitchen chairs out onto to lay beach towels under and over to create a fort for me to hide out and read in, the budding ground cover my father had painstakingly planted once it became clear grass would never survive in the dry soil, the little rocks my cat loved to roll in when they were heated by the afternoon sun, the rose bush in the corner where my first dog was buried.

The morning he died was the first — and one of only three times to this day — I had ever seen my father cry. It was Easter Sunday morning, when I was six, and while I sat at the coffee table in the den, my knees curled up under the wood my father had crafted — a place I spent thousands of hours making art over the years, producing so much of it my parents affectionately nicknamed me “fire hazard” — several of our neighbors gave up their holiday morning church or party plans, left their own children to be watched by others, came over with shovels and a wheelbarrow and, without even being asked, helped us commit a small misdemeanor, and bury our dog. It was a wordless, selfless kindness the like of which, when I was that young, I had never before seen, and have seen very rarely since. When I think of what it means to call yourself someone’s neighbor, I think of that morning.

The paint colors of the house itself — white and blue-gray — were unchanged, but one of the owners after us had painted over the distinctive red door. It had been a point of pride of my father’s, after he’d stubbornly fought the neighborhood council for months to get the color approved, and had always been used as a reference to anyone who came to visit: “It’s the blue and white house on the corner. Look for the red door.”

The paint colors of the house itself — white and blue-gray — were unchanged, but one of the owners after us had painted over the distinctive red door. It had been a point of pride of my father’s, after he’d stubbornly fought the neighborhood council for months to get the color approved, and had always been used as a reference to anyone who came to visit: “It’s the blue and white house on the corner. Look for the red door.”

I sat in my idling car, my eyes roving over every part of the façade, bombarded by memory. I saw my bedroom window, the window of my father’s home office, the living room window our Christmas tree’s lights once winked out of from between the curtains. The garage door behind which my father’s photo lab was built, where I’d learned to first use a camera, how to paint with light.

I thought back to my final weeks in the house, during which I photographed it obsessively; I was sure somehow I would forget everything about it once I stepped out the door, and wanted to record every detail. The living room carpet I’d built villages of Polly Pockets across, and rolled all over with my cat; the bar area that had never actually functioned as a bar, and ultimately filled with boxes of school and art papers and tracing paper animation studies; the kitchen counter my mother taught me to bake at; the sliver of parquet floor between the kitchen and den where I played elaborate games of marbles, as only a bizarre only child like me could have concocted, listening to my father’s records; the dust motes that would linger near the hallway banister upstairs as the sun set.

The bedroom that was mine; the room I did my beloved schoolwork in, the room I used our first home computer in and wrote horrendous fanfiction on as a teenager, the room I recovered from severe injury in, the room I looked out of in silence at the sky at sunset, my room, my room. My room. After leaving it, I never made a space mine again until over 10 years had passed.

Strangely, as I pulled away, my last thought was of the photo my father had taken of me, as I was going around attempting to preserve everything, not understanding that some part of me was trying to preserve the memories better, too; knowing my family and my home were splintering around me, in a way that would never be recovered. Things eventually would become better in other ways — my parents would get along better, my mother would be happier again, I would find a city to call mine — but I didn’t know this then. Maybe he also knew that, once we moved out, he and I would never have the sort of relationship as a family as we did under that roof; from this point on, we would exist in each other’s lives only as visitors. I would have no home in that city again.

He took the camera he had given me out of my hands at the top of the stairs, as the sun set, trying to catch the same perfect light I saw filtering through the windows behind the hanging lamp, and took the last photograph he ever took of me. I am tired out from weeks of packing up 17 years of a life, and my eyes are a little wet, though he cannot see this behind my glasses, nor would I ever have let him; my hair, uncharacteristically, is down in loose, messy waves around my shoulders; my smile is fleeting and sad. I know that when I take it back from him, I will walk down the stairs for the last time, and drive away, never to return. I look as if I might disappear from the picture if you look long enough. I look as though I am already gone.

A dear friend of mine is very fond of this piece, and when I came across the photos from the time period mentioned toward the end of it while organizing some files on one of my external hard drives, and though I’m no writer, I thought I might as well post it here, too, and include some of them. I realized, while browsing through them for the first time in many years, how closely my younger self had managed to capture the feel of my old house and life; I focused on small things I wanted to remember that might be less likely to remain than larger memories, details much to do with the way certain types of light during certain times of day came through which curtains, or struck which wall — the light in that house; it was so beautiful, especially during the golden hour. I even photographed myself a little, in a very specifically teenage-girl sort of way (bizarre, angled close-ups; it’s a common theme, when young women are attempting to figure out exactly what we really look like, coming of age in a society that objectifies and examines us so harshly and closely). Somehow, younger me knew exactly what sort of strangely personal images I’d want to revisit over a decade later, which I found oddly comforting to discover.

(Originally written December 2015, referencing an October 2015 visit to my hometown that included an impromptu solo drive through my childhood neighborhood. Personal photographs from April-June 2004.)

I circled back around and finally stopped at the place I’d saved for last: my old house. The front yard had been rendered nearly unrecognizable; a gangly, garish palm tree, of all things, now towered over it.

I circled back around and finally stopped at the place I’d saved for last: my old house. The front yard had been rendered nearly unrecognizable; a gangly, garish palm tree, of all things, now towered over it.

The paint colors of the house itself — white and blue-gray — were unchanged, but one of the owners after us had painted over the distinctive red door. It had been a point of pride of my father’s, after he’d stubbornly fought the neighborhood council for months to get the color approved, and had always been used as a reference to anyone who came to visit: “It’s the blue and white house on the corner. Look for the red door.”

The paint colors of the house itself — white and blue-gray — were unchanged, but one of the owners after us had painted over the distinctive red door. It had been a point of pride of my father’s, after he’d stubbornly fought the neighborhood council for months to get the color approved, and had always been used as a reference to anyone who came to visit: “It’s the blue and white house on the corner. Look for the red door.”